The fields are almost bare now. The last sheaves of barley and oats have been gathered, and the cattle have been driven in from the uplands. The air smells of smoke, peat and frost. Every family knows the dark half of the year is coming. It is a time when the veil between life and death is at its thinnest, and survival depends on preparation.

In Ireland, the old Celtic calendar divides the year into two halves. Beltane on the 1st May is the start of the light half (summer) and Samhain on the 1st November is the start of the dark half (winter). So this night, 31st October, is not just a festival, it’s the eve of the new year. Samhain falls between the Solstice at midsummer and the Solstice at midwinter. It is the turning of the year. And the preparation for the coming darkness and cold, the deadness and silence to be, is to honour our ‘right relationship’ with the sacred. That means to honour our ‘right relationship’ with each other, the land, the spirits of places and nature and the earth herself, the winds and her directions, those who came before us and those who will come after, the rivers and rocks, the blood and bones of the earth, and the Gods and Goddesses who heal us and protect us and the Sacred of the Otherworld, from which all things come.

“We honour our ‘right relationship’ with each other, the land, the spirits of places and nature and the earth herself, the winds and her directions, those who came before us and those who will come after and the rivers and rocks, the blood and bones of the earth.”

Ours is an oral tradition. We share our knowledge through generations by the spoken word and, so, we are wisdom keepers. We are at Tara, in Meath. Stories told around fires for generations taught us what sacred land this is and we gather at this place at this special time to honour that land and the ancestors and the sacred that resides here.

As dusk falls, the hearths in every roundhouse are extinguished. Smoke curls into the cold twilight. Soon, the single great fire will be lit on the sacred hill at the Cnoc na Teamhrach, the ‘Hill of Tara’.

Tuatha Dé Danann

We did not always have ‘right relationship’ and order. There was a time when chaos and death was everywhere. These lands were ruled by the dark sea giants, the Fomorians, who relished wasteland and plague. Then came the Tuatha Dé Danann, the tribes (tuatha) of the goddess Danu, who brought order and ‘right relationship’ and peace. The Tuatha Dé Danann were gods and goddesses, some say from another civilisation under the sea known as Atlantis. They brought with them a magical stone, the Lia Fáil, or the Stone of Destiny, or the Speaking Stone, and they gifted it to the land and it stands today on this Hill at Tara. The Tuatha Dé Danann were skilled in the arts and law and were radiant. The Fomorians were chaotic, deathly and dark. The Fomorians were led by Balor, a giant with one ‘evil eye’ in his forehead that brought death to anyone he gazed upon.

“The Tuatha Dé Danann brought order and ‘right relationship’ and peace. They were skilled in the arts and law and were radiant.”

In an attempt to bring peace, there was a marriage between Cian of the Tuatha Dé Danann and Ethniu daughter of Balor of the Formorians to unite the two races. They had a son, Lugh, or Lú, after whom the place land of Louth was named. Lugh was known as ‘the shining one’ and he was gifted in all things. But peace did not last and the chaos of the Fomorians meant famine, death, lawlessness and oppression. The Tuatha Dé Danann wanted peace and plenty and so war was put upon them. Lugh, led the Tuatha Dé Danann into battle against the Fomorians and he killed his giant one-eyed evil grandfather, Balor, bringing peace and abundance to the land.

Later, when we mortals arrived, Lugh, along with all of the Tuatha Dé Danann, retreated into the land and the hills of the Otherworld to become the sídhe (the faerie people of majestic rank).

Ceremony of the Crowning of the High King

Many ceremonies happen here at this sacred place. The Hill is also known as the Seat of the High Kings, for it is where every High King of Ireland is crowned.

“The would be king stands upon the Lia Fáil, the Speaking Stone, or the Stone of Destiny. If that man is the rightful king, the sacred stone cries out beneath his feet, ensuring order and ‘right relationship’ between the land and the leader.”

— Credit to photographer Anthony Murphy, at www.mythicalireland.com

When a would be King walks upon the royal hill of Tara to be crowned, he first steps upon the Lia Fáil, or the Stone of Destiny, or the Speaking Stone, the sacred stone gifted by the gods of the Tuatha Dé Danann. If that man is the rightful king, the sacred stone cries out beneath his feet, ensuring order and ‘right relationship’ between the land and the leader.

A King is not king by virtue of lineage necessarily, but by ‘right order’. He receives the title only when the goddess of the land, Ériu, or Éire, who is the sovereignty, the ultimate true leader of the island, gifts it to him.

At these king ceremonies, Lugh emerges out of the mists, a shining horseman, the god of kingship and the god of Light, to bring the king into sovereignty with the earth. The would-be king follows the shining one to a phantom feast hall beneath the earth. There he meets a beautiful woman holding a golden cup. “To whom shall this cup be given?” the woman asks. Lugh answers, “To this man, for he is King of Ireland.” The woman serves the man a draught of ale. This is the bringing together of the mortal and the spirit in alliance with order and peace. After he drinks, she recites a long prophetic poem listing all the future kings who will reign at Tara. This is truly sacred land.

“Lugh, the god of Light, emerges out of the mists, to bring the king into sovereignty with the land, at a phantom feast hall beneath the earth. There he meets a beautiful woman holding a golden cup. “To whom shall this cup be given?” she asks. Lugh answers, “To this man, for he is King of Ireland.” The woman serves the man a draught of ale. This brings the mortal and the spirit in alliance with right order and peace.”

But tonight we do not celebrate kings, or leadership. Tonight we honour the dead.

Samhain Ceremony

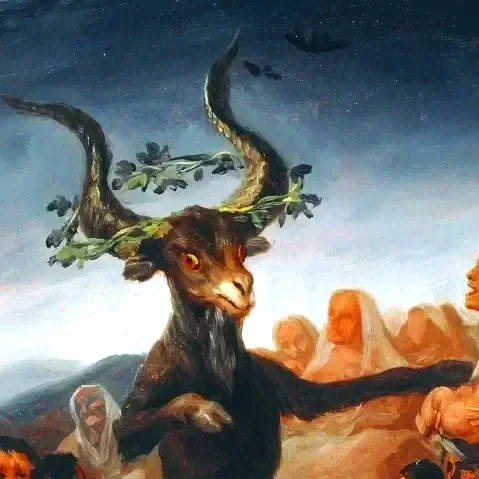

As the night deepens, we put on animal masks and furs from wolf coat or stag hide, the skulls adorned with antlers or horns. Some daub ashes or soot on their faces. It’s dangerous to walk unmasked tonight. Spirits abound, and if you must leave home, you disguise yourself to confuse them, or to join in their revels unseen.

Groups of youths may go from house to house, “mumming” or “guising”, performing small plays or songs in exchange for food or drink. Their laughter carries across the dark hills. It’s both a ritual of inversion and a mockery of fear. By imitating the mischief and malevolent spirits, the children rob them of their power.

“Groups of youths will go from house to house, ‘mumming’ or ‘guising’, performing small plays or songs in exchange for food or drink. Their laughter carries across the dark hills. It’s both a ritual of inversion and a mockery of fear. By imitating the mischief and malevolent spirits, the children rob them of their power.”

Tara is the ritual centre of the island. Earthworks and ceremonial enclosures here date back thousands of years. From here, the Druids, our learned class, our priests, shamans, healers, poets, storytellers and astronomers, lead the rites.

Druids have four main areas of knowing. They know how to talk with spirits, follow the stars and the moon cycles, they know herb craft and they are masters of ceremony. The Master of Ceremony for Samhain has already had the children of the roundhouses gather brightly coloured stones and pretty crystals and feathers to line the ceremonial route.

We follow the feather stone path to the ceremony site on the Hill. We are dressed in guises, to merge with the animal spirits that guide us and to honour them and we gather around the central pit with a tower of unlit wood. We have brought offerings for the fire, to thank the gods of fire for the purification it brings. Some of us have carvings, made during the year, of wood tied with grasses onto which they put their moist tears of suffering, to give to the fire so the fire would take it and heal it and sadness would release its hold.

The Master of Ceremony for Samhain calls in the spirits of our ancestors, the gods and goddesses that protect us and our lands that provide for us and recalls our histories, exclaims our truths and honours our dead who live among us. A quiet descends.

“As the night deepens, we put on animal masks and furs from wolf coat or stag hide, the skulls adorned with antlers or horns. Some daub ashes or soot on their faces. It’s dangerous to walk unmasked tonight. Spirits abound, and we disguise ourselves to confuse them.”

When the Master of Ceremony kindles the fire with sacred oak, a murmur ripples through the crowd. Sparks rise into the sky. The fire ignites and crackles, spits and snaps, the branches sounding like they are being snapped underfoot. Soon we are warmed by it, the ceremonial fire that is both a beacon and a prayer to the gods for protection and to the spirits for peace. The fire is ablaze, heating us all and allowing the reverence of the sacred to be present with us and in us. We each, in turn, give our offerings to the fire and give it thanks. The aliveness of the fire’s presence against the dark sky holds us in trance. Slowly we begin to sing and chant our prayers and the Master of Ceremony gently plays out a rhythm on his bodhrán drum. We are grateful and prepare to leave for the feast that awaits.

Families and druids take embers from this communal blaze to rekindle their home hearths, a symbol of the renewal of life, unity and the sun’s power. “The fires of Samhain were lit upon the hill of Tlachtga, and from them every fire in the land was kindled anew.” — Irish Dindshenchas (Place Lore)

Rituals and Offerings to the Spirits

Tonight, the veil between worlds is at its thinnest. The Áes Sí, the fairy folk, ancestors, and otherworldly beings, roam freely. To honour them and avoid mischief or illness, we leave offerings outside our homes. Bowls of grain, butter, honey, milk, or ale, pieces of bread or meat from the feast. The offerings are placed by the doorway, the threshold between worlds, where the dead enter through. Sometimes a place is set at the feast table for departed kin.

“Otherworldly beings roam freely. To honour them and avoid mischief or illness, we leave offerings outside our homes. Bowls of grain, butter, honey, milk or ale, pieces of bread or meat from the feast. The offerings are placed by the doorway, the threshold between worlds, where the dead enter through.”

Once the fires are bright and the offerings made, we feast. Our tables are laden with roasted meats and stews thick with barley, turnips, and herbs. Oatcakes and honeyed breads. Apples, nuts, and ale; the fruits of the harvest. During the feast, we have games of divination, bobbing for apples, seeking to know fate for the coming year. Apples floating in water, if caught with the teeth, foretells luck or love. Hazelnuts, the nuts of wisdom, are put side by side in the fire to see if a lovers bond will last. If the two nuts burn together, the love they represent will stay. If they pop apart, the match is doomed. Before bed, older children will eat small sweetened cakes in silence, hoping to dream of their future spouse. We echo the rituals of the druids for seeking knowledge on fertility, survival and destiny.

Liminal Space

After the feast, silence falls again. The fire crackles low. The elders pour a libation of ale onto the earth. This is the moment of crossing. To us, death is not final, but part of a cycle. Life, death and rebirth are the eternal rhythm. Samhain is a hinge upon which that rhythm turns. The dead return to visit the living. Ancestors are honoured, not feared. But not all spirits are to be trusted.

We gather around and the elders tell stories, of the Sluagh, the restless dead who fly on the wind, or the Púca, a shapeshifting trickster, often seen as a black goat, who may lead travellers astray. The day of the Púca is November 1, the newest day of the year, and we leave part of the crop in the fields, or grain outside, for this spirit to earn his blessings and not his curse. The poets and storytellers tell of the great heroes and gods, of the Tuatha Dé Danann, of Lugh, of the Morrígan, the goddess who presides over war and fate. Fires crackle as tales of love, loss and rebirth fill the air. Our lives are rinsed by the end of year clarity.

“The elders tell stories, of the Sluagh, the restless dead who fly on the wind, or the Púca, a shapeshifting trickster, often seen as a black goat, who may lead travellers astray.”

Everything in Samhain is dual, death and rebirth, darkness and light, danger and blessing.

The Dawn of the New Year

After sleep, as dawn breaks on November 1, the community gathers the smouldering embers of the sacred fire and each family carries its flame home and rekindles the hearth. Smoke rises once again from every roof. It is the first day of the Celtic new year. The living have made it through another Samhain without harm. The ancestors have been honoured, and the household has been renewed. Now comes winter, a season of storytelling, craftwork, silence and stillness, of gestation in the dark as we wait for the light to return, for the bursting forth of new life in Spring, at Imbolc, in February. The Celtic world moves forward again, through darkness toward rebirth.

“To honour the dead,

to light the dark, to mark

the turning of the year.

This is Samhain’s heart.”