Come here, Grandchild, and sit with me while the fire is warm. I will tell you why this day feels heavy for our people. Tonight I will tell you the story about the celebration that the others call ‘Thanksgiving’.

I will tell you where it comes from, and how we, the Wampanoag, were there at its beginning. You have heard the stories in books and schools, smooth and bright like stones shaped too long in water. But to know your people, is to know the true story, because you belong to this land, and the land remembers. Let me tell it to you as the elders told it to me, and the ancestors told it to them, before.

Long before the ships of the white men came to these shores, our people lived with the land as kin. We are the People of the First Light. We rise with the first sun, as our name says. The light brushes the tops of the trees and warms the waves beside our villages. It touched our fishing weirs and the gardens we planted with our hands. It shines on our children running among the corn and the elders sitting in doorways weaving stories into the air.

We plant, we hunt, we fish and we gave thanks not once a year, but always. To us, thanks is not a day. It is a way of living with the land and being.

Before the white man came, our life had balance. We took care of this land, and her waters, and she took care of us. We planted corn, beans and squash together so each plant could help the others grow. We put fire to the underbrush in the forests in spring so that new plants, the ones the deer like best, would come back in strength. We fished when the herring returned and thanked them for their journey. We hunted when the seasons called for it and thanked the animal's spirit for its life and, after, buried her bones with honour. We gave thanks not by saying the word, but by giving respect to all living beings, the earth, the waters, the wind, sun and sky, the spirits of this land and to the ancestors and by putting gratitude into each act we do for the gifts as they are given to us. With honouring, we live in union with the land, we put our love into these forests and hills, treat this living, breathing land and her bounty with care. We live with and in her with respect.

“ We gave thanks, not by saying the word, but by giving respect to all living beings, the earth, the waters, the wind, sun and sky, the spirits of this land and to the ancestors and by putting gratitude into each act we do for the gifts as they are given to us. With honouring, we live in union with the land, we put our love into these forests and hills, treat this living, breathing land and her bounty with care. We live with and in her with respect.”

For us, gratitude is every day, not once a year. Every step upon the earth, every drink from the stream, every berry picked, every breath of cold morning air, we bring thanks. This is how our people care for the land. This was the rhythm of our lives, the teachings handed down from our elders to our children.

But dark times came, a great sickness from the white man ships that traded along the coast. We had no defences against these new diseases, nothing to shield our bodies or our spirits. It moved like a shadow we could not see and took many of our people. It swept through our villages like a cold wind that would not warm again. Many of our families fell, whole communities gone. Villages that had sung with life and where laughter had lived, fell quiet. Fires that had burned for generations went out.

Patuxet, the place where the English would build their town, stood empty when they arrived. We were still grieving when their ship appeared on the horizon. When people today go to that place, they do not hear the echoes, but the earth remembers every voice lost there.

When the white man stepped out of their ship, they walked on land still heavy with our sorrow. The stories told about this day often start with the arrival of the white man, as if nothing existed before. But our lives, our joys, our griefs, our ways, our deep care for this land, all was already here. We were here. We had been here since our ancestors saw the first sun.

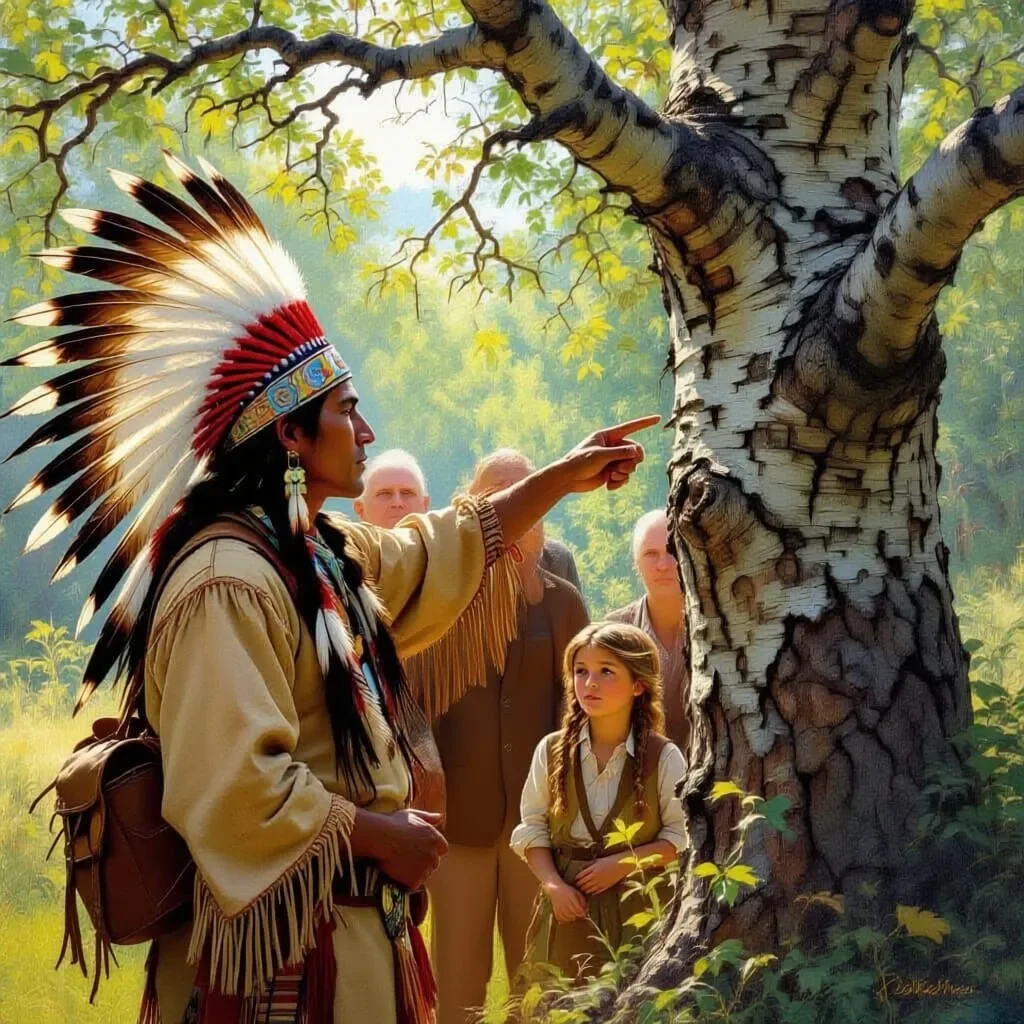

When the white man came ashore, at first, our people watched them from the trees. The strangers spoke a strange tongue and carried dangerous weapons that we had not seen before. They were weak with hunger and cold and unready for this land. They dug into storage pits where our dead had kept their corn. We watched them in silence.

“They knew nothing of this land. They did not know where the springs were, what roots to dig, what tree bark heals swelling, or pain, how to take the sweetness from the maple, what the soil needed, what the winter winds could do. Tisquantum knew. Through him, our people could speak with the newcomers. Slowly, the newcomers learned new ways and we came into agreements.”

They knew nothing of this land. They did not know where the springs were, what roots to dig, what tree bark heals swelling, or pain, how to take the sweetness from the maple, what the soil needed, what the winter winds could do.

We did not know how to proceed. Our people had been diminished by the sickness, our numbers had grown small, and threats from neighbouring nations were strong. Among us, was our sachem, named Ousamequin. He was a man of wisdom and he carried the weight of decision for our people. He weighed every path before him. He understood that these newcomers, though few, could become powerful allies or dangerous enemies. He knew that if we helped them to survive, we might create balance and safety for our own people. And so he chose the path of alliance, though it was a path neither simple nor without risk.

There was another man among us, Tisquantum, a young man of our village, strong and clever, whose life had taken many painful turns. Years before, he and 26 of our people were stolen, by a white man named Hunt, and taken across the great sea against their will. Tisquantum was sold as a slave and kept for years. While he was gone, he learned the ways of the white man and their tongue. Somehow, he escaped and made his way back. When he came home, he found his village emptied by the sickness and all of his family dead. Ousamequin asked him if he would be willing to be a bridge between our people and the newcomers.

“We did not know how to proceed. Our people were diminished by the sickness, and threats from neighbouring nations. Among us was Ousamequin, a man of wisdom, who carried the weight of decision for our people. He weighed every path before him. He understood that these newcomers could become powerful allies or dangerous enemies. If we helped them to survive, we might create balance and safety for our own people.”

The white men knew nothing of this land, Tisquantum knew the soil, the rivers, the fish, the deer. Through him, our people could speak with the newcomers. Tisquantum’s life had been stolen from him by Hunt, yet he used what he had learned to help our people survive and to try to keep balance. Slowly, the newcomers learned new ways and we came into agreements.

After the newcomers had lived through their first planting season, first cold moon, first warm wind returning, first time of ripening, and their first Harvest Moon, they gathered together to rejoice their survival. They fired their muskets in loud celebration, a sound that carried across the fields and into our villages. Such noise could mean many things, possibly danger, or victory, or alarm. Ousamequin gathered 90 of our men to go to see what was happening. It was not a small group and we were not invited, but we did not know the reason for the firing of the loud noises and we came out of caution and responsibility, and care for our people.

When we arrived, the newcomers were celebrating, but with little food to offer for so many. So our hunters went out and returned with five deer, which they shared. We moved between their settlement and our camps over several days, talking, observing, maintaining our agreement. There were moments of friendliness, yes, and moments of shared laughter even. There were misunderstandings too, and careful watching. It was not a single feast where everyone sat at one grand table, becoming friends. It was a meeting between two peoples learning how to live beside one another, stepping cautiously, neither fully trusting nor fully at ease.

“When we arrived, the newcomers were celebrating, but with little food to offer. So our hunters went out and returned with five deer, which they shared. There were moments of friendliness, yes, and moments of shared laughter. There were misunderstandings too, and careful watching. It was not a single feast where everyone sat at one grand table, becoming friends. It was a meeting between two peoples learning how to live beside one another, neither fully trusting nor fully at ease.”

When people today speak of that gathering as if it was the birth of joyful friendship, they tell a hollow truth. The meeting was real, but it was complicated, and soon the relationship changed.

There were newcomers who treated us with respect, who honoured the agreements, who spoke with kindness. But many did not. Some broke their promises. Some let fear turn them cruel and we saw the shadow of the soul-crossing in their eyes, like they were dead inside their hearts. These things are not easy to speak of, but you must know them. If the story is to be whole, it must include the parts that ache.

Then, more foreigners came. One ship became many. They built more houses, then more towns. They cut down forests where our hunting trails had twined for generations. They fenced land that had always been shared. They laid claim to rivers as if they had made them. And with each new settlement, our world grew smaller.

And, in time, war came, a terrible war that scarred both our people and theirs. The land shook with violence. Villages burned. Lives ended that should have had many seasons left. Our people suffered greatly and we lost family, land, safety and voices that can never be replaced. So, we do not say ‘thanks’ on this day, but we remember what was lost, we mourn our dead, the loss of the land we love, the great suffering that came to all of us after the settlers came.

This is the true history of the Thanksgiving of which the white man rarely speaks. They pause the tale at the moment of shared food and never tell of the horrors that followed. But you must know, our story does not end there. It does not end in silence and it does not end in defeat. We are still here.

“Then, more foreigners came. One ship became many. They built more houses, then more towns. They cut down forests and our hunting trails. They fenced land that had always been shared. They claimed rivers as if they had made them. And with each new settlement, our world grew smaller.”

You, little one, are part of this. Every time you speak our language, every time you sit at a drum, every time you hear a story like this and carry it with you, you honour the ones who came before and the ones who fought to keep our people alive.

So when people speak of Thanksgiving, remember what it truly was, not a beginning of friendship in the way the outside world imagines, but a moment of careful connection during a fragile and changing time. Remember that our people were generous, thoughtful and wise. Remember that we offered help even when our own hearts were grieving. Remember that we acted with strength, not submission. And that what followed was hard, but that we endured.

Through all that pain, through all those years, our ancestors held on. Some held on by remembering the language, even when the white man tried to silence it. Some taught our stories in whispers. Some stayed on this land no matter what pressure or outcome came. Some held on by adapting, by surviving storms that would have broken lesser people.

And so we remain. We walk the same shoreline where our ancestors walked. We gather quahogs where they gathered them. We plant the same three sisters that fed our families centuries ago. We sing songs that were silenced but never truly died. And now, in your generation, our language breathes again. The words that once fell quiet have returned to the mouths of our children. Do you feel how powerful that is?

And remember that above all that, gratitude, real gratitude, has always been our way. Not because of one day in a year, but because of how we are. When you rise in the morning and greet the sun, you give thanks. When you taste the first berry of the season, you give thanks. When you help your family, learn from your elders, play with your friends, you give thanks. It is woven into our lives.

“And remember above all that gratitude, real gratitude, has always been our way. Not because of one day in a year, but because of how we are. When you rise in the morning and greet the sun, you give thanks. When you taste the first berry of the season, you give thanks. When you help your family, learn from your elders, play with your friends, you give thanks. It is woven into our lives.”

This is the truth that I wanted to tell you tonight. A clear truth, a loving one, an honest one. A truth that is yours to carry, to own. You are of a people that is strong and wise, gentle and proud, and with a deep knowing of this land and all she has carried.

The world calls it Thanksgiving, but for us, it is different. The white man celebration may have begun here, but we do not forget what happened. For us, it is not a celebration, but a Day of Mourning.

When we walk to the hill in Plymouth to honour those who suffered and those who endured we carry our ancestors’ grief with us, but also their strength.

Come now, feel the earth beneath you. Put your hands on it. She remembers all things. She holds the footsteps of those foreigners who walked into our villages generations ago. She holds the footsteps of our people who planted the fields, of our children who laughed in the summer grass, of the warriors who protected our people and of the elders who carried the stories. And now she holds your footsteps too.

And, in time, you can give these truths to your children, and your children’s children, and they can know that our ancestors live among us and that we hold their wisdom in our hearts, and that wisdom will live on in the hearts of our people for generations to come.